One morning when I was nine, I was eating breakfast and hating the yolk from the fried eggs. I had always found a way to dump it into the trash without Florence Dupont, my foster mother, knowing.

This time her daughter saw me. So when I went to take out the trash, I was met by Florence’s flat hand across my face.

She slapped me so hard my ears rang, and I tasted blood bubbling in my mouth.

Then she grabbed my head and stuffed my face down into the garbage. While she was yelling at me to find the eggs and eat them, I passed out.

Eventually, I ended up at the California Youth Authority, the last stop before adult prison.

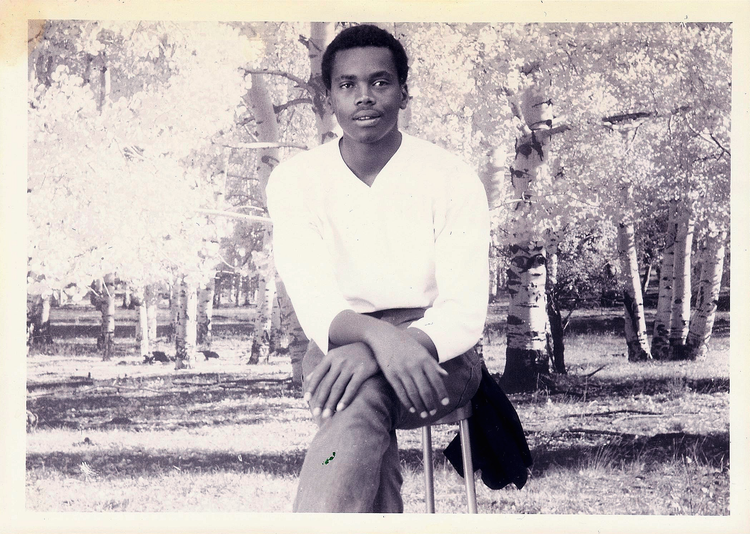

There I met Hershey, a counselor whose support helped me take myself seriously enough to earn a diploma.