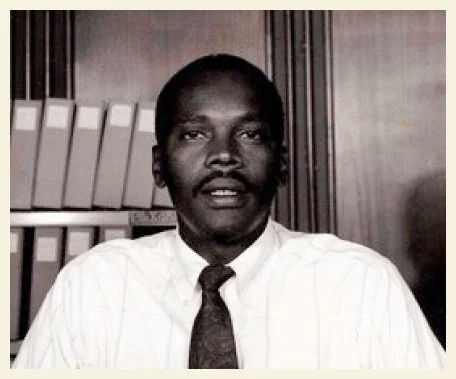

the story of jarvis’ case

Jarvis Masters arrived in San Quentin in 1981 at age 19, convicted of armed robbery.

Four years later, in 1985, officer Sergeant Howell “Dean” Burchfield was murdered within the prison walls, stabbed to death at night on the second tier of a cell block.

At the time, Jarvis was locked in his cell on the fourth tier.

Although many were suspected of conspiring to murder Sgt. Burchfield, only three were tried. One was accused of being the "spear man"—of actually stabbing the sergeant. Another, was accused of ordering the killing.

Jarvis was accused of sharpening a piece of metal which was allegedly passed along and used to make the spear with which the officer was stabbed. This weapon was never found. If found, it would have proven Jarvis innocent.

In one of the longest trials in California history, all three defendants were convicted of murder and of conspiracy to murder, but their sentences varied. One jury recommended the death penalty for the spear man, but the trial judge reduced his sentence to life without parole because of his youth and his relatively minimal record.

Another jury could not reach a verdict on the older man's sentence. The District Attorney declined to re-try him, and he was also given life without parole.

After hearing about Jarvis' criminal history, that same jury sentenced Jarvis to death. Jarvis' lawyers asked the trial judge for leniency, also on the basis of his youth — he was only 23 when the crime occurred, just two years older than the convicted spear man.

But the judge denied this request and sent Jarvis to death row.

He has been there since 1990, waiting for his appeals to be heard.

Jarvis’ appeals focus on serious charges of prosecutorial misconduct and errors of the court that prevented a fair trial and denied Jarvis the opportunity to prove his innocence.

To that end, in 2005, while still waiting on his appeal, Jarvis and his team filed a habeas corpus petition in the California Supreme Court, arguing that he is entitled to a new trial because the State violated his constitutional rights in the first trial—not the least of which is new evidence showing that he was innocent yet was still convicted.

This claim that Jarvis is factually innocent was presented along with other constitutional violations, such as the fact that the State presented false evidence.

The Court usually denies these petitions in one-sentence orders. But in response to Jarvis' petition, the Court took the extremely rare step of issuing an Order to Show Cause (OSC) demanding that California state prosecutors tell the Court why Jarvis should NOT be entitled to a new trial.

The Justices' willingness to consider such claims by Jarvis before his appeal was rare and perhaps unprecedented. It was a glimmer of hope.

An evidentiary hearing was ordered in 2008, and a 13-day hearing was held in 2011. A special referee appointed by the California Supreme Court agreed that false testimony was presented at Jarvis’ original trial. However, she was unwilling to believe the subsequent recantations of his witnesses, calling them “unreliable” since they were “career criminals.”

In 2015, the California Supreme Court heard arguments from the initial 2001 appeal and in 2016 upheld Jarvis’ conviction. A hearing on the habeas appeal Jarvis filed in 2005 was delayed until 2019, and was subsequently denied.

In 2020, Jarvis’ case entered the federal courts, where he filed a petition for habeas corpus. In 2024, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California denied him the writ of habeas corpus. Jarvis will now appeal to the Ninth Circuit Court and continue considering all legal remedies.

There is no justification for the terrible murder of Sgt. Howell Burchfield and no way to ignore the suffering imposed on his family and friends.

Neither is there justification for the incarceration of Jarvis Masters, an innocent man living all these years in the shadow of a death sentence.

case Timeline

At 19, Jarvis is convicted of armed robberies and sentenced to 20 years.

Sergeant Howell Burchfield is murdered at San Quentin prison. Jarvis, who was locked in his cell on another tier at the time of the murder, was subsequently accused of fashioning the murder weapon.

After his wrongful conviction, Jarvis remained in solitary confinement at San Quentin for 21 years.

Of the three men convicted, Jarvis is the only one sentenced to death for his alleged role in the crime.

Shortly after his death sentence, Jarvis reads “Life in Relation to Death” by Tibetan Buddhist lama His Eminence Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche. Jarvis writes to Rinpoche who eventually visits him at San Quentin. Rinpoche encourages Jarvis to harness his intelligence and use it in service of others.

Jarvis takes the formal refuge vows of Buddhism with Rinpoche and devotes his life to Buddhism.

Jarvis publishes his first book “Finding Freedom,” a firsthand account of harrowing prison stories and Jarvis’ role of peacemaker as he tries to put compassion into action amid chaos and squalor.

Jarvis connects with renowned Buddhist nun and author Ven. Pema Chödrön who becomes a cherished friend, spiritual teacher, and long-time advocate for Jarvis.

Jarvis filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus to the California Supreme Court. Habeas corpus is the legal mechanism to present new evidence that did not come to light at the original trial. Jarvis’ lawyers argue that Jarvis is entitled to a new trial because the State violated his constitutional rights in the first trial. Jarvis’ initial appeal is still pending.

After more than two decades in solitary confinement (longer than any other inmate in San Quentin history at the time), Jarvis is transferred to the death row general population unit.

A special referee is appointed by the CA Supreme Court and ordered to hold an evidentiary hearing to determine whether the State presented false evidence at Jarvis’ initial trial and whether newly discovered evidence was indicative of Jarvis’ innocence.

Jarvis publishes his second book, a memoir, “That Bird Has My Wings.” Like his first book, it is also handwritten with pen fillers and paper. Jarvis reflects on his grim childhood with parents addicted to heroin, an abusive foster family, his road to incarceration, and his eventual embracing of Buddhism.

The special referee conducts a 13-day evidentiary hearing over the course of 4 months.

The special referee acknowledges that false testimony was presented at Jarvis’ original trial. However, she is unwilling to believe the subsequent recantations of these witnesses, calling them “unreliable.” Ironically, the testimony of these same inmates was enough for the Court to sentence Jarvis to death in 1990, but its recantation was not enough evidence for exoneration.

Jarvis collaborates with The Truthworker Theatre Company to help develop a striking theater production, which examines the impact and practices of solitary confinement in the US. Jarvis is passionate about working with youth and at-risk populations, in addition to helping other inmates.

Nearly 25 years after the original trial, the CA Supreme Court finally hears oral arguments from Jarvis’ initial direct appeal filed in 2001.

The Court upholds Jarvis’ death penalty conviction, denying his initial direct appeal.

Gov. Gavin Newsom states that he believes there are innocent people in death row, issuing a moratorium on capital punishment in California.

Petition for writ of habeas corpus that was filed in 2005 is denied. Jarvis’ appeals now move to the federal courts.

International law firm Kirkland and Ellis LLP takes on Jarvis’ case pro bono, representing him in federal habeas and other post-conviction proceedings.

Jarvis filed a petition for habeas corpus in the federal district court in the Northern District of California

Jarvis presents virtually as a speaker at the 2021 Black & Buddhist Summit. Through the lens of his own spiritual practice and while imprisoned, Jarvis details the transformative impact Buddhism can have on people of color.

After almost two years of inaction from the district court, Jarvis filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings, essentially requesting that the court rule in favor of Jarvis’ habeas petition.

Jarvis’ legal team requested the Federal District Court of Northern California to grant the writ of habeas corpus and exonerate Jarvis. The court will issue a written order.

After 42 years at San Quentin, Jarvis is transferred to Sierra Conservation Center, in Jamestown (Tuolumne County), 130 miles away. He is among the last men to leave East Block as part of California’s mandatory Condemned Inmate Transfer Program meant to physically dismantle the nation’s largest death row.

The U.S. District Court denied Jarvis’ motion for judgment on the pleadings of his federal habeas appeal.

The U.S District Court denied Jarvis' federal habeas petition. The ruling underscores the systemic challenges of exoneration for the wrongly convicted, despite significant evidence of innocence. Jarvis will appeal and continue his pursuit of justice.

You can Help Jarvis' Case

Since 1973, 200 people who were wrongfully convicted have been exonerated from Death Row in the United States.

Unfortunately, many more like Jarvis, are still here awaiting justice. Please help set them free.